A-one, two, three, FOUR!

A-one, two, three, FOUR!

By Stuart Barter (Chime)

The first sound on the first album by The Beatles is not guitar-riff, or an up-beat on the snare drum, but Paul McCartney’s voice counting to four. One, two three FOUR, he yelps, and thus begins the catalogue of the most successful pop band in history. It’s a small moment, but it demonstrates one of the most simple, and fundamental link between music and maths.

You don’t have to look hard to find more examples of counting in pop music, it’s all over Rock Around The Clock (five, six, seven-o-clock, eight-o-clock rock!, anybody?), and also the first sound in Wilson Picket’s Land of A Thousand Dances, and the links go much deeper than that.

In a recent article in the Daily Telegraph, Ivan Hewett, inspired by mathematician Marcus du Sautoy examines how patterns, sequences, groups and shapes inform the worlds of both music and maths. The two disciplines have much more in common than you might think, and there are plenty of ways of bringing these links out in your lessons with primary school children, and increasing their enjoyment and understanding of both.

Counting and numbers

As Paul McCartney so memorably demonstrated, counting is a fundamental musical skill. With young children, you can build their understanding of number and placement and their pulse awareness by counting along to music. For an extra challenge, you could ask the children to count how many bars there are in a certain piece of music (“One, two, three, four; Two, two, three, four; Three, two three, four; Four, two, three, four” etc.). For older children, you can improve their multiplication and division skills in a similar way. Use a backing track or clap a regular pulse for the children and have them count to the beat. Ask them to replace all numbers divisible by ‘5’ with a clap; then all sounds divisible by ‘3’ with a stamp. Which numbers require both a stamp and a clap? As I’m sure you can see, the game has endless extensions with different sub-divisions and sounds replacing the numbers.

In fact, the very backbone of music is built around numbers and division. The musical bar is made up of a certain number of beats (typically four or three), and the notes within them are sub-divisions of the bar (e.g. minim=two beats; crotchet=1beat; quaver=half a beat; semi-quaver = quarter of a beat; and so on). You can illustrate this to children practically, ask them to clap the quaver beat over a 4/4 backing track; how many quavers in each bar? How many crotchets? They can then experiment making patterns of the different note values in each bar, ensuring each bar adds up to four beats, before clapping the patterns to a backing track or pulse. Which patters sound the most pleasing? Which are easiest to play? This will help not only their division skills, but also the core musical skills of pulse, rhythm and listening.

Numbers can also greatly help provide structure for children when writing music. Can the children write a melody on the glockenspiels that is 12 bars long? Splitting the 12 bars into three groups of four will help with this greatly, as will restricting their choice of notes to the five black notes on the keyboard (the keys in the top half of the glockenspiel). Shape and structure are crucial to music, and this approach to composition will help the children understand this, and get them used to the role of numbers in music. They’ll then need their musical skills to assess how pleasing their compositions sound!

Patterns

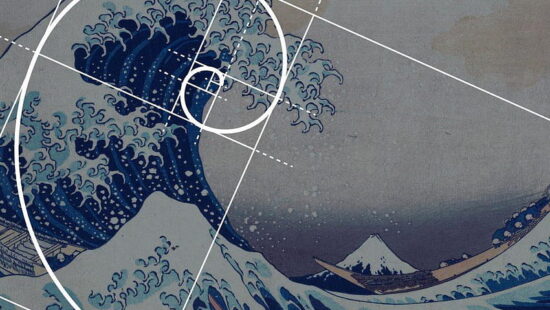

The maths curriculum requires children to understand axes of symmetry, and to perform shape transformations. These principles are great for musical composition and improvisation. Can you play a rising melody for the children, which they have to sing back in its mirror image (descending in the same pattern)? This could form the starting point for a short composition based on melodies or shapes that are then turned backwards or mirrored. A symmetry composition, if you like. Can some of your shape transformation work which the children produce on paper form the basis for a piece of music, with the children imitating the lines and patterns using instruments.

In fact, there is a long tradition of using pictures and images to notate music, rather than traditional music notation. They are known as graphic scores, and consist of patters, shapes and colours to be responded to musically. Graphic scores can range from very simple groups of images, to much more visually detailed and complex examples. Composing from pictures can help children’s understanding of the properties of shapes. Can the children produce five long sounds, to represent the five sides of a pentagon? With shapes that have sides of different sizes, can they represent these different lengths with sounds of different lengths. You could ask the children to ‘play a shape’ and the other children guess what shape is being played (e.g. four sounds of equal length = a square).

There are patterns in every aspect of music, and listening and responding to music will help the children recognise and memorise patterns without them even realising it. Play a song of the children’s choice and lead some simple repeating rhythms or movements for them to copy. You will nearly always find yourself grouping the patterns around the structure of the music, and it is surprising how quickly children recognise the patters and are able to perform them back from memory. You can also ask the children to lead a warm-up activity like this, allowing them to practice their own musical patterns and sequences independently.

Ivan Hewett’s Daily Telegraph article begins with a quotation from the philosopher Leibniz, who describes listening to music as “The mind counting without being conscious that it is counting”. This nicely summarises how valuable the link between music and maths is in the classroom, and indeed the power of performing arts in general. So many of the learning opportunities in performance are present without the children’ realising it. Try some of the activities suggested above, and help the children count, and more, without even knowing it’s happening.